An Implementation of Prototyping OOP

In the class/instance system above, it is necessary to design the complete behavior of a class before you can make any instances of the class. This is okay for top-down design, but not great for experimentation. Here we sketch the implementation of a prototyping OOP system: You make an object, tinker with it, make clones of it, and keep tinkering. Any changes you make in the parent are inherited by its children. In effect, that first object is both the class and an instance of the class. In the implementation below, children share properties (methods and local variables) of their parent unless and until a child changes a property, at which point that child gets a private copy. (If a child wants to change something for its entire family, it must ask the parent to do it.)

Because we want to be able to create and delete properties dynamically, we won’t use Snap! variables to hold an object’s variables or methods. Instead, each object has two tables, called methods and data, each of which is

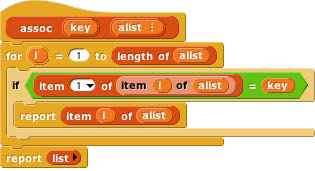

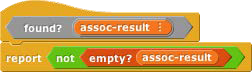

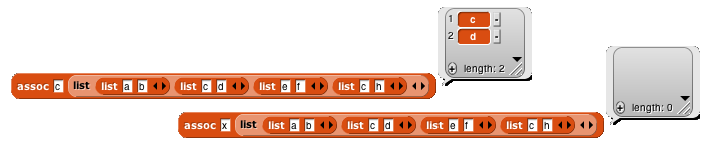

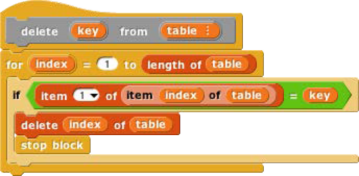

an association list: a list of two-item lists, in which each of the latter contains a key and a corresponding value. We provide a lookup procedure to locate the key-value pair corresponding to a given key in a given table.

There are also commands to insert and delete entries:

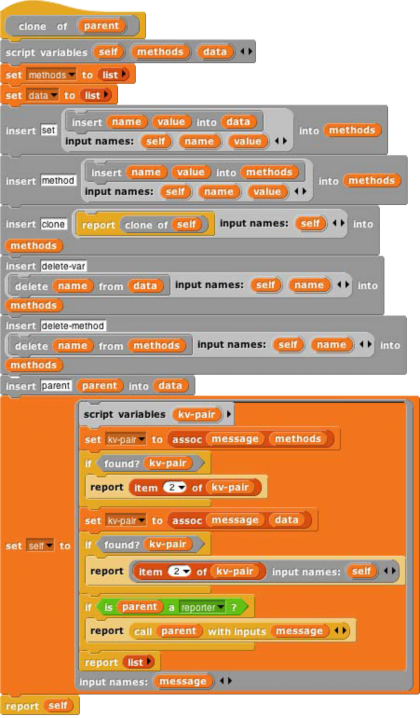

As in the class/instance version, an object is represented as a dispatch procedure that takes a message as its input and reports the corresponding method. When an object gets a message, it will first look for that keyword in its methods table. If it’s found, the corresponding value is the method we want. If not, the object looks in its data table. If a value is found there, what the object returns is not that value, but rather a reporter method that, when called, will report the value. This means that what an object returns is always a method.

If the object has neither a method nor a datum with the desired name, but it does have a parent, then the parent (that is, the parent’s dispatch procedure) is invoked with the message as its input. Eventually, either a match is found, or an object with no parent is found; the latter case is an error, meaning that the user has sent the object a message not in its repertoire.

Messages can take any number of inputs, as in the class/instance system, but in the prototyping version, every method automatically gets the object to which the message was originally sent as an extra first input. We must do this so that if a method is found in the parent (or grandparent, etc.) of the original recipient, and that method refers to a variable or method, it will use the child’s variable or method if the child has its own version.

The clone of block below takes an object as its input and makes a child object. It should be considered as an internal part of the implementation; the preferred way to make a child of an object is to send that object a clone message.

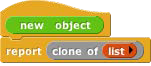

Every object is created with predefined methods for set, method, delete-var, delete-method, and clone. It has one predefined variable, parent. Objects without a parent are created by calling new object:

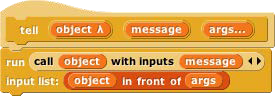

As before, we provide procedures to call an object’s dispatch procedure and then call the method. But in this version, we provide the desired object as the first method input. We provide one procedure for Command methods and one for Reporter methods:

(Remember that the “Input list:” variant of the run and call blocks is made by dragging the input expression over the arrowheads rather than over the input slot.)

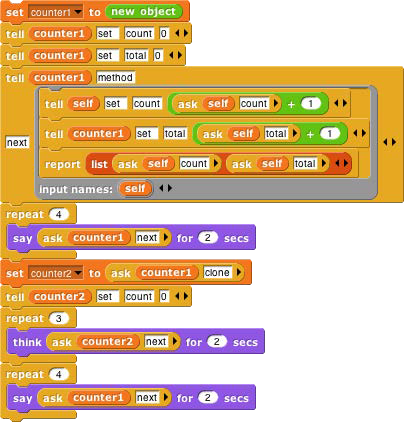

The script below demonstrates how this prototyping system can be used to make counters. We start with one prototype counter, called counter1. We count this counter up a few times, then create a child counter2 and give it its own count variable, but not its own total variable. The next method always sets counter1’s total variable, which therefore keeps count of the total number of times that any counter is incremented. Running this script should [say] and (think) the following lists:

[1 1] [2 2] [3 3] [4 4] (1 5) (2 6) (3 7) [5 8] [6 9] [7 10] [8 11]

The Outside World

The facilities discussed so far are fine for projects that take place entirely on your computer’s screen. But you may want to write programs that interact with physical devices (sensors or robots) or with the World Wide Web. For these purposes Snap! provides a single primitive block:

This might not seem like enough, but in fact it can be used to build the desired capabilities.